WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD

It has become a truism that we

are living in an age of political extremes.

A lot of media attention has been lavished, particularly in the de facto two-party state that is England,

on the re-emergence of socialism as a political force and the decline of

neoliberal managerialism on the left, as exemplified by SYRIZA’s rise to power

in Greece (if not its style of government in practice) and the surprisingly

strong performance of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in last year’s UK general

election. On the other side we have an

increasingly prevalent nationalist, nativist and authoritarian strain within

right-wing politics; see, for example, Viktor Orban’s “illiberal democracy” in

Hungary, the Law and Justice party in Poland and, on the other side of the

Atlantic, Donald Trump. But there is

also a third political tendency positing itself against both, and enjoying

electoral success in some countries.

This “Third Way” is a “radical centrism”, but a radical centrism which,

concerningly for political leftists such as myself, has shifted to the right in

two notable cases wherein centrist movements were able to form national

governments; Italy and France.

A political movement can be

defined as centrist because its policies sit consistently in an ideological

space equidistant between mainstream left- and right-wing thought, because its

manifesto comprises a mixture of traditionally left- and right-wing policies, or

because its platform is vague or empty enough that no judgement can be made as

to its overall alignment. The largest

party in this year’s Italian general election, the Five Star Movement (M5S),

founded in 2009 by comedian and blogger Beppe Grillo, is an example of the second

kind. The M5S’s electoral manifesto was the

eclectic slate of promises and affirmations you would expect from a party which

operates in large part on the principle of direct democracy (a form of

decision-making it advocates for the nation as a whole). Traditionally left-wing policies such as support

for same-sex marriage and measures to tackle climate change sat alongside a

pro-Putin foreign policy, Euroscepticism and no small amount of

anti-immigration posturing. Underpinning

these policies, the M5S’s campaign was characterised by the avowed

anti-corruption and anti-establishment standpoint that originally propelled it

to prominence, the idea that “politics as usual” no longer works.

The momentum this generated among

a disillusioned Italian public has now taken the movement into government. However, in order to command a majority in

parliament, the M5S took the decision to form a coalition with the far-right

Lega party, and the early months of the administration have been characterised

principally by the hardline anti-immigrant rhetoric of the Lega and its leader

Matteo Salvini, with the M5S offering precious little leftist action to

countermand this.

Last year’s big centrist win in

European politics, meanwhile, was the election of Emmanuel Macron as president

of France. Macron, a former investment

banker who served in the cabinet of the Socialist president Francois Hollande

between 2012 and 2016, ran on a platform he variously described as “neither

right nor left” and “both right and left”.

Macron’s agenda included socially liberal ideas (he is in favour of

equal marriage), but also economically right-wing pro-business policies that

pledged to lower corporation tax and “unblock France” by loosening the

country’s famously tight labour laws and making it easier for companies to fire

workers. How far you deem his manifesto

to be truly centrist depends on your own politics, but there is no doubt he was

treated as such by both the French press – Le

Figaro described him as a “radical centrist” – and French voters. Macron drew support from moderate liberal and

moderate conservative elements of the electorate, beating the candidates of the

two formerly dominant centre-left and centre-right parties in the first round

before comfortably seeing off the far-right leader Marine Le Pen in the run-off

(though many leftists who voted for him in the second round held their noses

when doing so, seeing preventing a Front National government as the most

important thing, as when Jacques Chirac defeated Marine’s father Jean-Marie in

2002).

However, since taking power

Macron has been criticised for a drift to the right, particularly on national

security and immigration; the very issues over which the M5S seem to have ceded

control to the far-right Lega in Italy’s new coalition government. The issue, then, that leftist voters who

plump for centrist candidates must face is this, as demonstrated by both

examples I have covered; that there is always a risk that the governments they

form will be, to adapt Macron’s phraseology, “more right than left”, whether

because the rightist elements of their platform become more prominent over

time, or because they must form alliances with conservatives to remain in

power. Left-leaning voters who voted

Liberal Democrat in the UK in 2010, only to see them go into coalition with

David Cameron’s Conservative Party and help preside over a brutal austerity

regime, found this out to their cost (including myself, I am ashamed to admit).

A good amount of attention has

been paid by critics to works of fiction featuring totalitarian regimes of the

extreme left (The Party in George Orwell’s Nineteen

Eighty-Four) or the far right (the Nazi-esque Norsefire movement in Alan

Moore’s V for Vendetta). But I’d like to argue that in our present

political moment, there’s interest to be had in examining a couple of fictional

politicians – one dictator and one would-be dictator – each of who espouse an

outwardly centrist platform. Harry Saxon

in Doctor Who and Masayoshi Shido in Persona 5 do not rise to power by

promising full communism, collectivism, a patriotic war, mass deportations,

brutal suppression of anti-nationalist elements, or any far-left or far-right

policy. Rather, they gain popularity

through an anti-corruption, anti-establishment “big tent” approach that draws

huge swathes of the public (socialist, liberal and conservative) to their side

while simultaneously masking the true nature of their political project. Both of these fictional works seem to

advocate suspicion of centrist political platforms on the grounds that

politicians that seek to appear as “all things to all people” may be doing so

simply because it makes it easier for them to seize power through electoral

success, and thus easier to execute a hidden agenda. It is this suspicion that left-leaning

voters, if they wish to guard their nations against the depredations of the

political right and far right, would do well to adopt.

In “The Sound of Drums”, the

penultimate episode of the 2007 series of Doctor

Who, the Doctor (David Tennant) and his companion Martha (Freema Agyeman)

discover that his nemesis, The Master (John Simm), has become Prime Minister of

the United Kingdom under the alias Harry Saxon.

Saxon is depicted as a wildly popular political outsider who has been

able to gain public shows of support from a wide range of political and public

figures, including celebrities like Sharon Osborne and the boyband McFly, and

the Conservative MP and latter-day Strictly

Come Dancing contestant Anne Widdecombe (someone whose endorsement, believe

it or not, would once have been a significant boon to an up-and-coming politico). Once established as PM, Saxon uses a summit

with the American president as an opportunity to seize absolute power by

killing the president, revealing himself as the Master, and calling forth a

race called the Toclafane (the degraded remnants of humanity from one hundred

trillion years in the future) to massacre one tenth of the Earth’s population;

a literal decimation. The series’ final

episode, “Last of the Time Lords”, set one year later, opens with the Master having

transformed the entire planet into a munitions factory from which to wage

unending war on the rest of the universe, with humanity as his slaves. The centrist democrat has taken his place as the most terrible of authoritarians.

Saxon’s appeal to voters is

framed not only in terms of his charisma – one character refers to him as a

“modern day Churchill” – and his status as a political outsider who excelled

outside of parliament as a top university athlete, novelist and businessman,

but in terms of his centrism. We learn

that he is a former Defence Secretary, but not whether he served on behalf of

Labour or the Conservatives. His

political movement is centred on himself rather than any political party or

ideology. In this, he is similar to

Macron, who ran for president first and formed an official movement later

(tellingly, his parliamentary bloc, En Marche!, shares his initials). We can characterise Saxon’s run for Prime

Minister as centrist in character because of a scene in which he meets with his

cabinet, for two reasons.

Firstly, a member of his front

bench outright tells him they have “very little” in the way of policy, implying

that Saxon’s manifesto was vague enough to appeal to voters across the

political spectrum. Secondly, Saxon,

just before he gasses his team to death, berates them as “wet, snivelling

traitors”: “As soon as you saw the vote swinging my way, you abandoned your

parties and you jumped on the Saxon bandwagon”.

The fact that he says “parties” rather than “party” is significant,

because it shows that his political movement was something that both Labour and

Conservative politicians could feel comfortable joining. Saxon’s platform must therefore be a form of

radical centrism hitherto unseen in Britain’s habitually polarised politics;

even at the height of New Labour’s “Third Way” years, defections from the

Conservative Party were very rare.

It could be argued that Saxon is

able to accomplish this rise to power not because of his centrist alignment but

through a rhythmic signal he transmits into the brains of Earth’s population; the

“sound of drums” from the episode title.

However, the Doctor explicitly states that the signal is not a form of

mind control: “No, no, no, no, no. It's

subtler than that. Any stronger and people would question it. But contained in that rhythm, in layers of

code, Vote Saxon. Believe in me. Whispering to the world.” The sound of drums, then, would not be enough

to propel Saxon to power, only to dull people’s inquisitive tendencies to the

point where they fail to question a biography the Doctor characterises as an

obvious forgery, and instead see him as a charismatic “saviour” figure. But why not use a stronger form of mind

control? Moreover, we might ask why the Master

feels the need to put on the Harry Saxon charade when he has an army of six

billion deadly Toclafane with which he could easily enslave the world without

having to go through the rigmarole of impersonating a human and getting himself

elected Prime Minister of the UK.

The answer to both questions

seems to be that the Master wants to prove a point to the Doctor; that the

humans he loves so much will willingly put a dangerous megalomaniac into high office

if said megalomaniac outwardly appears to them as a handsome, charismatic

figure, even if their manifesto contains little to nothing in the way of

substantive policy. In this way Doctor Who provides a critique of those

who vote for centrist candidates based primarily on their personality and assume

that when in government their vague manifestos will coalesce into an

administration amendable to them; the risk when voting for a centrist

politician is that their seeming moderate nature is just a tool to get them

elected, and their true agenda may be gravely oppressive.

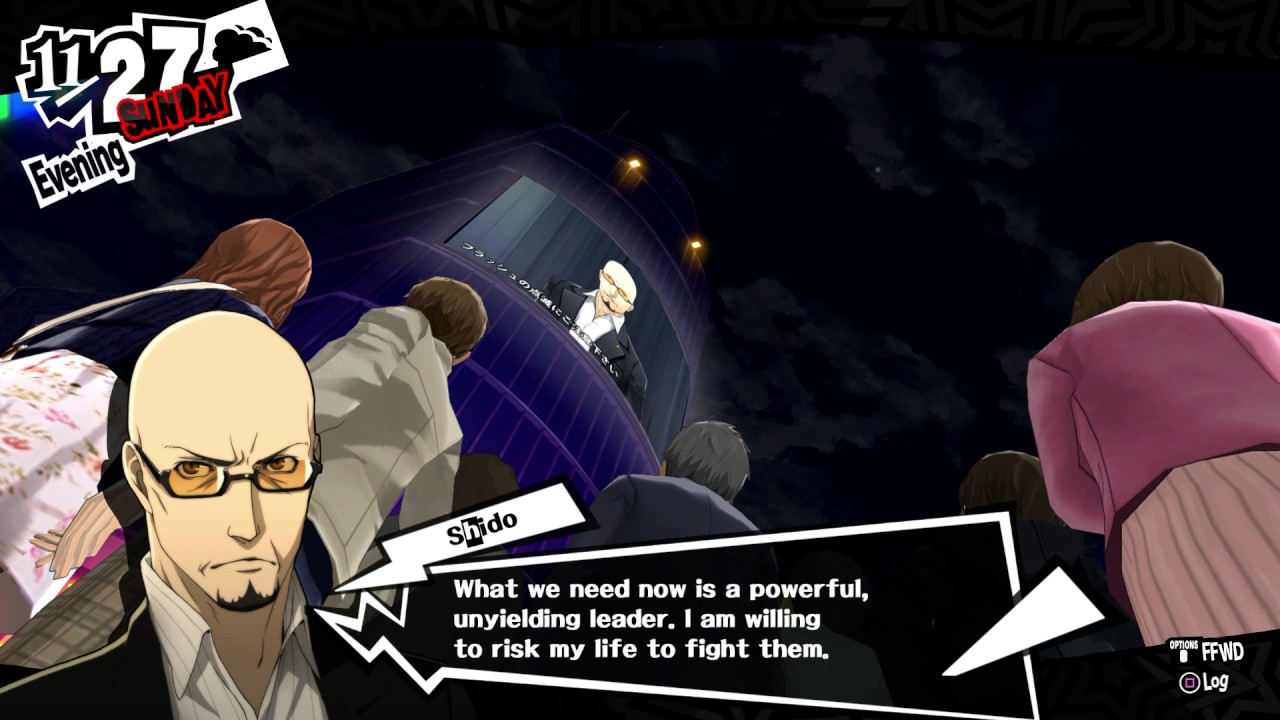

This dynamic can also be seen in Persona 5 (2016), the latest RPG in the

popular Shin Megami Tensei video game

series. Put simply, the plot of Persona 5 is as follows: a group of

teenagers (and the obligatory anthropomorphic anime cat) known as the Phantom

Thieves find that they have the ability to enter spaces called “Palaces”, which

may be defined as the “distorted desires” of evildoers given physical form in a

dimension adjacent to but distinct from reality (the “cognitive world”). By battling and defeating malevolent “Shadow”

versions of these people within their Palaces, the team is able to “change

their hearts”, which leads them to confess and atone for their crimes in a

public show of abjection.

At its core, Persona 5 is a story about abuse of

power, and has some quite profound things to say about the way in which the

habitually rigid social, economic and political hierarchies within present-day

Japan create the conditions in which these abuses can happen. Our high school heroes are either social

rejects (two young men written off as delinquents, a brilliant hacker confined

to her bedroom by depression and trauma) or high-achieving pupils struggling to

cope with the dues exacted by their low position within the particular

hierarchy in which they find themselves (a promising painter, an aspiring

model, the heiress to a huge corporation, an honour student run ragged by her

responsibilities as class president).

The first few villains with which they do battle are figures who prey on

such vulnerable youngsters by exploiting the imbalance of power between them: a

volleyball coach who physically abuses his team and demands sexual favours from

its female members; an artist who passes off the work of his students as his

own; a petty gangster who extorts money from teenagers. In all of these cases, a distorted desire –

lust, the lure of fame, love of money – gives rise to a “Shadow self”. By changing the hearts of these characters,

the Phantom Thieves hope to redress the balance in favour of justice.

Eager to make a difference not

just on a local but a national level, and also to solve the riddle of a

mysterious figure who has been causing havoc in Tokyo by entering people’s

consciousnesses within the cognitive world and turning them into rampaging

maniacs, the Phantom Thieves turn their attention to bigger fish: a CEO who

exploits his workers, a detective who is less concerned with truth than with

securing a conviction. Eventually their

investigations lead them to the man responsible; an ambitious politician called

Masayoshi Shido (voiced by Shuichi Ikeda in the Japanese original, Keith

Silverstein in the English dub). Through

bringing the incidents to an end by bumping off the lackey who was destroying

people’s minds on his behalf, while at the same time pinning the blame on the

Phantom Thieves and having them locked up, Shido hopes to gain enough

popularity to become Prime Minister of Japan, and to maintain his grip on power

in perpetuity by using his mastery of the cognitive world to manipulate the

minds of his political opponents and turn them psychotic.

Like Harry Saxon, Shido’s professed

political platform can be described as centrist. Before resigning in order to launch his

candidacy for Prime Minister, he served in the cabinet of the Liberal

Co-Prosperity Party; a clear fictional analogue for the Liberal Democratic

Party, the right-wing party that has ruled Japan virtually uninterrupted since

its formation in 1955. However, his new

political movement, the United Future Party (a name which simultaneously evokes

an outward desire for compromise and its founder’s innate tendency to

totalitarianism), espouses a Saxonesque centrist platform centred around its

leader’s charisma and carefully constructed image as a political outsider. National security features heavily in Shido’s

election campaign in the form of his promise to bring the Phantom Thieves to

justice, which may suggest that Shido is running as a specifically conservative

“law and order” candidate (issues of national security generally figuring more

prominently in right-wing than left-wing manifestos). Yet the main tenor of his candidacy is

based on much the same appeal as that of the M5S, one which chimes with the

concerns of both leftist and rightist voters; politicians have become corrupt

and bureaucratic, “politics as usual” has failed, but a saviour has

arrived. His pledge to halt the mental

shutdowns functions less as a signifier of right-wing ideals than an example of

the sort of efficacy a Shido government can provide in enacting reforms that

will please and benefit voters of all stripes.

For the most part, Shido sticks to slogans such as “social reform”, “a

new future of dreams and hope”, “abundant wealth and luxury”; vague promises

divorced from any outward leftist or rightist ideology or even (as with Harry

Saxon) any policy details regarding how these would be achieved.

However, the mind control Shido

exerts exceeds that of Saxon. Whereas the

Master drops the “Harry Saxon” pretence as soon as he gains power, Shido’s hold

over his nation’s voters survives even his disgracing. Following the Phantom Thieves’ defeat of the

Shadow Shido in his Palace, the real-life Shido begins to confess his crimes to

camera, before his aides cut the broadcast and he collapses into a coma. Yet the public seem not to care, or not to

have noticed; their main concern is whether Japan can survive without Shido as

Prime Minister. Their faith in their

totem remains undimmed. Eventually the

Phantom Thieves discover the reason; that Shido is merely a puppet of an

ancient deity called Yaldabaoth, a self-proclaimed “God of Control” who hopes

to remove any agency from the lives of human beings, and sees a Shido

dictatorship as a way of bringing Japan under its heel. More alarmingly, we learn that Yaldabaoth is

being helped in this by a Palace called Mementos, a gigantic cognitive

structure formed by the distorted desire not of one man but the entire human

race; the desire to submit, to give up responsibility for their own choices,

their own lives.

It is for this reason we can say

that Persona 5 represents a less

stinging critique of the Macronesque “centrist outsider” politician than does Doctor Who. In the latter the electorate’s sin is

credulity. They vote in their droves for

one of the universe’s most dangerous evildoers because they can neither see

through his disguise as a smooth, charismatic young politician, nor his

content-free centrist platform. Doctor Who explicitly diagnoses centrism

as a tool by which a tyrant may attain power.

In Persona 5, meanwhile, it is

more complex than that. Its villain’s

nefarious plan shares elements with the Master’s in “The Sound of Drums”/”Last

of the Time Lords” – mind control, centrist politics as a mask for evil – but

what is different is the role of the voters and the origins of their love for

their would-be dictator. The game’s

story makes clear that humanity’s desire to give up control to Yaldabaoth

(through voting for his agent Shido) does not arise ex nihilo; it is a distorted

desire, an amplified version of what is depicted as an inherent tendency

towards conformity and disengagement.

The people of Britain in Doctor

Who risk their freedom (and lose it for a time) because of their susceptibility

to centrist politics, but the people of Japan in Persona 5 risk their freedom because of their susceptibility to

authoritarianism. In Persona 5 centrism is a symptom rather

than the disease.

However, we may say that while Persona 5 provides a less damning

indictment of slavish support for centrist politicians than Doctor Who, it offers a more pessimistic

view of humanity’s political atavisms, one which we should consider in the

light of Macron and the M5S. In Doctor Who the Doctor not only defeats

the Master through a standard contrivance of the show’s writers (the human race

restores his sapped power by believing really, really hard in him), he erases any

trace of his genocidal regime from history.

By destroying the “paradox machine” through which the Master made it

possible for the Toclafane to travel back in time and murder their own distant

ancestors, the Doctor rights the chronology and sends the universe back to a

point in time just before the Toclafane made their appearance, foiling the

Master’s plan. By contrast, when the

Phantom Thieves defeat Yaldabaoth through that classic method of destroying

evildoers (an epic forty-minute RPG boss battle), they are under no illusions

that they have sired a new age of freedom and political consciousness. The desire to submit has become un-distorted,

the Palace it created is gone, but it is still there. We are forced to ask; how much of Shido’s

meteoric rise to the brink of the Prime Ministership was down to Yaldabaoth’s

machinations, and how much could he have effected without the supernatural

powers of a god?

Therefore, let us once again

consider Macron and the M5S. This essay

has focused mostly on the “bland” kind of centrist platform, the “all things to

all people” manifesto so devoid of actual proposals that voters can imagine

that the candidate’s government will be to their liking. But what of the “melange” type, the platform

featuring myriad proposals drawn from different political traditions? Or, to put it another way, what of the

rightist tendencies within centrism?

What are we to make of the left-leaning Macron voters who voted for him

even knowing his right-wing pro-business, anti-labour policies? Or the leftists who plumped for the M5S

knowing that, as per Italy’s proportional representation system, the prospect

of them going into government with a far-right party was a very real

possibility? How do we understand these

voting decisions when leftist candidates and movements were available? Is the desire for submission to right-wing

authoritarianism more widespread among centrist and even liberal and socialist

voters than they themselves would like to admit? Was the sound of drums necessary for the

likes of Matteo Salvini to ride his anti-immigrant ethos into the corridors of

power upon a tidal wave of “radical centrist” votes? Did Emmanuel Macron need a Yaldabaoth?

And, most importantly, who the

hell are the left’s Phantom Thieves?